2 Seconds of Colour

2015

A decapitated head continues to consciously register the world for two seconds. Indrė Šerpytytė’s 2 Seconds of Colour originated from a Google search for ‘Isis beheadings’. In less than a second, Šerpytytė was confronted with many millions of images. The speed, the effortlessness of the search, and the sheer number of results seemed offensive. Someone had been murdered in the most brutal fashion, and yet these images were being presented almost as if they were no more than scenes churned out as mass media. After a while, other equally traumatic images would be available. Another death, another war, expanding the archive. The effect of this might be desensitising. Yet such extreme images of violence have the potential to be unbearable, provoking shock or voyeuristic fascination – a fact of which Isis is fully conscious. The perceived widespread incapacity to respond in any critical way to such images might be better considered as the result of there being neither the time nor the space to process them. Wishing to avoid trauma, we avert our eyes.

Šerpytytė acknowledges this tendency to turn away or approach such imagery uncritically. She has maintained the importance of creating a body of work that might allow the viewer to confront violent events, offering the space to think about violence and its circulation in images interrogatively and contemplatively.

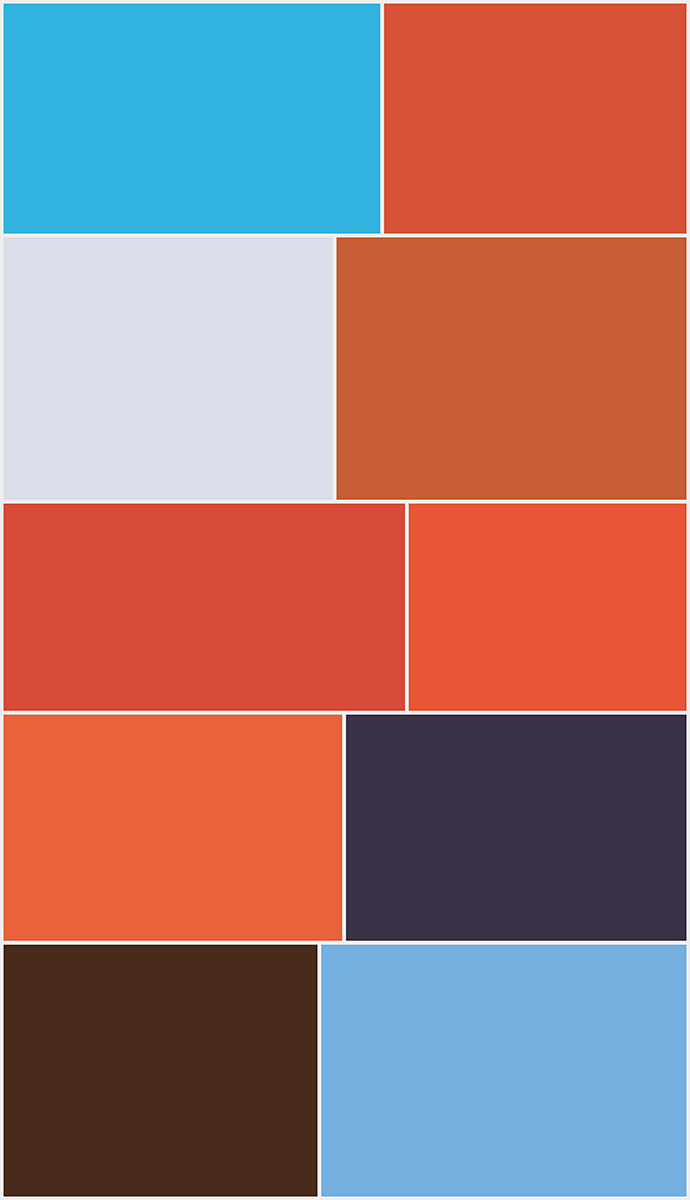

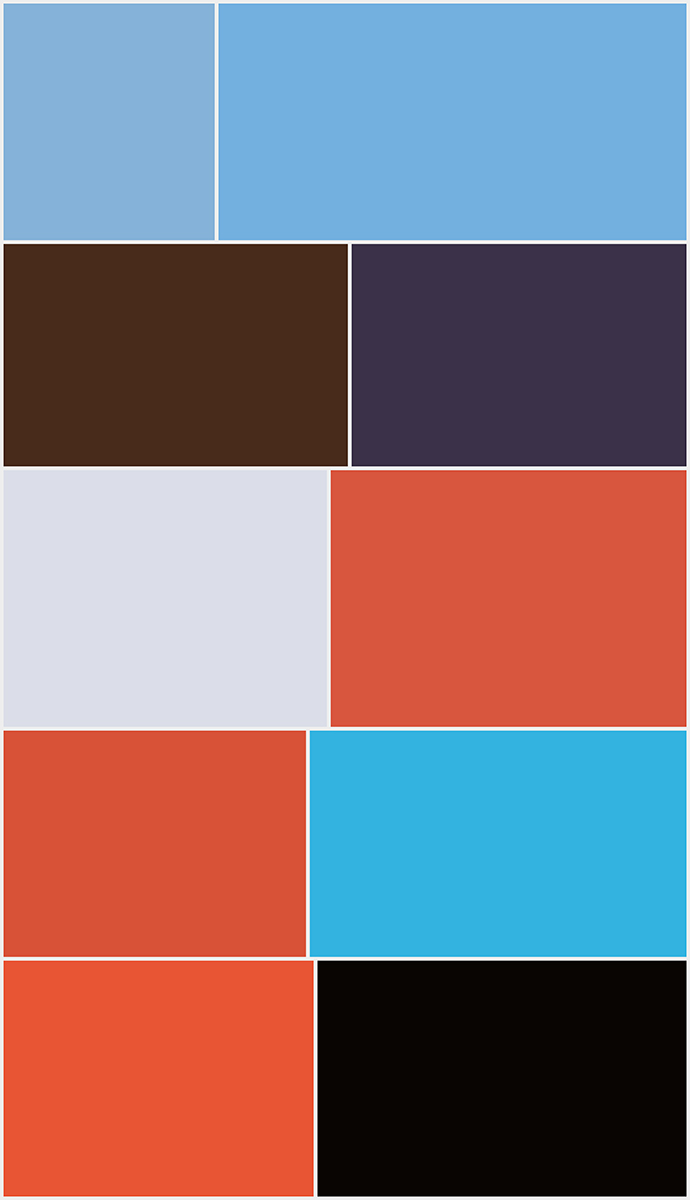

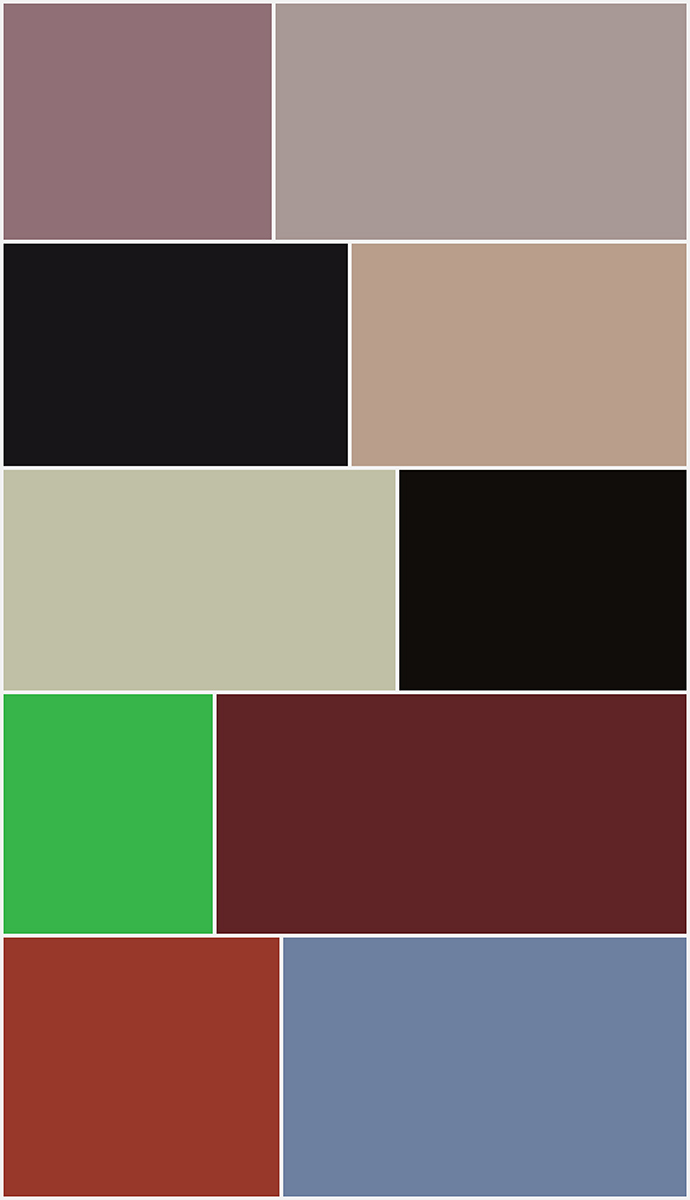

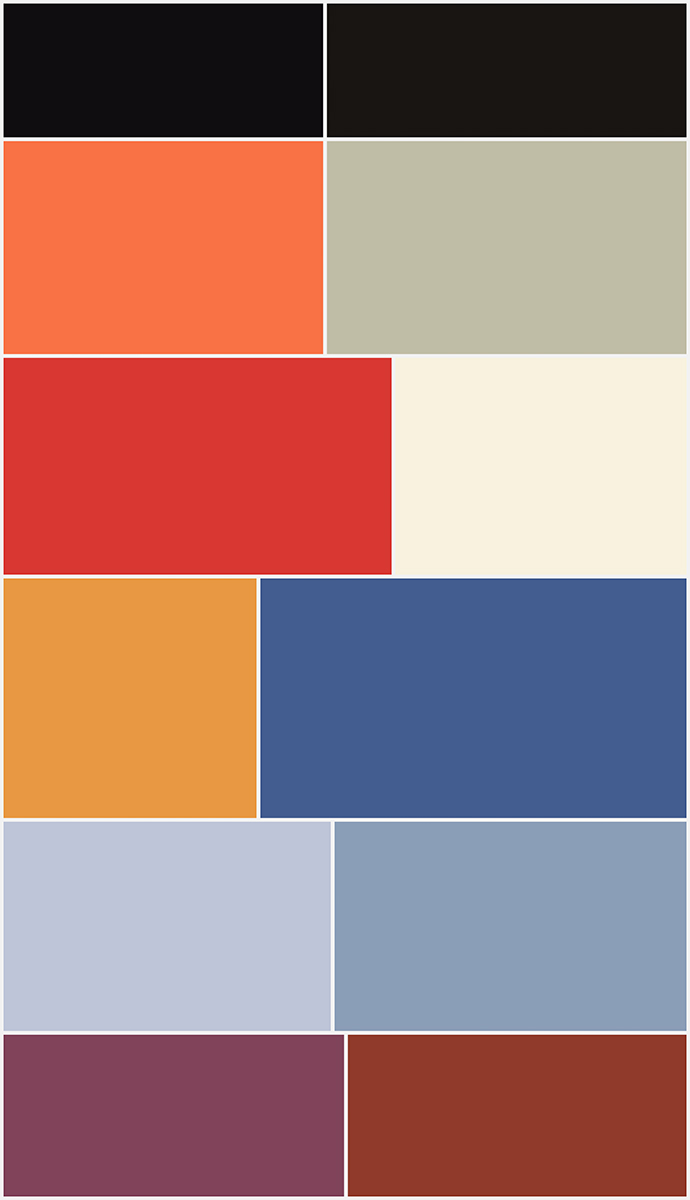

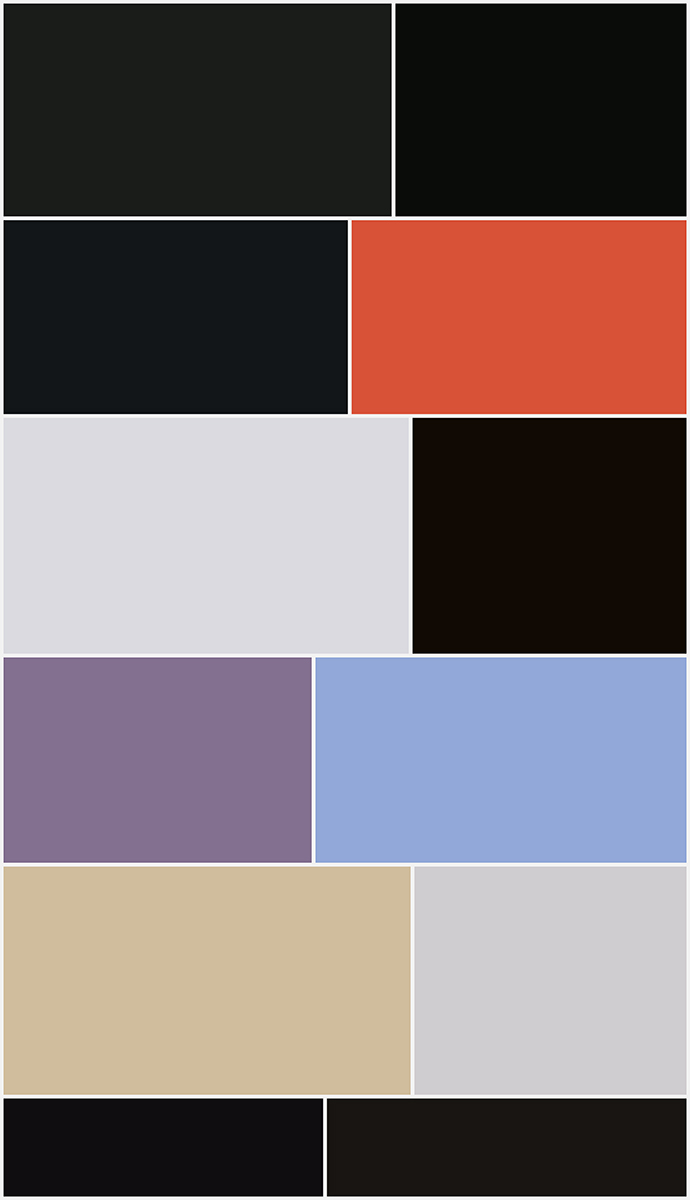

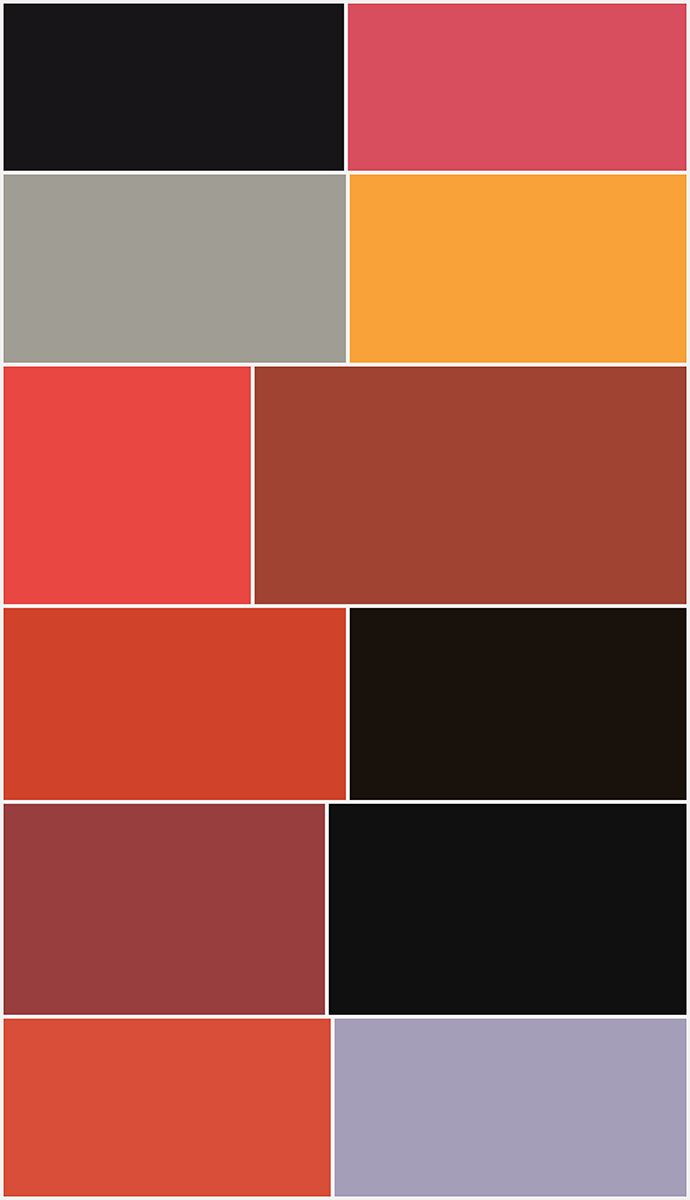

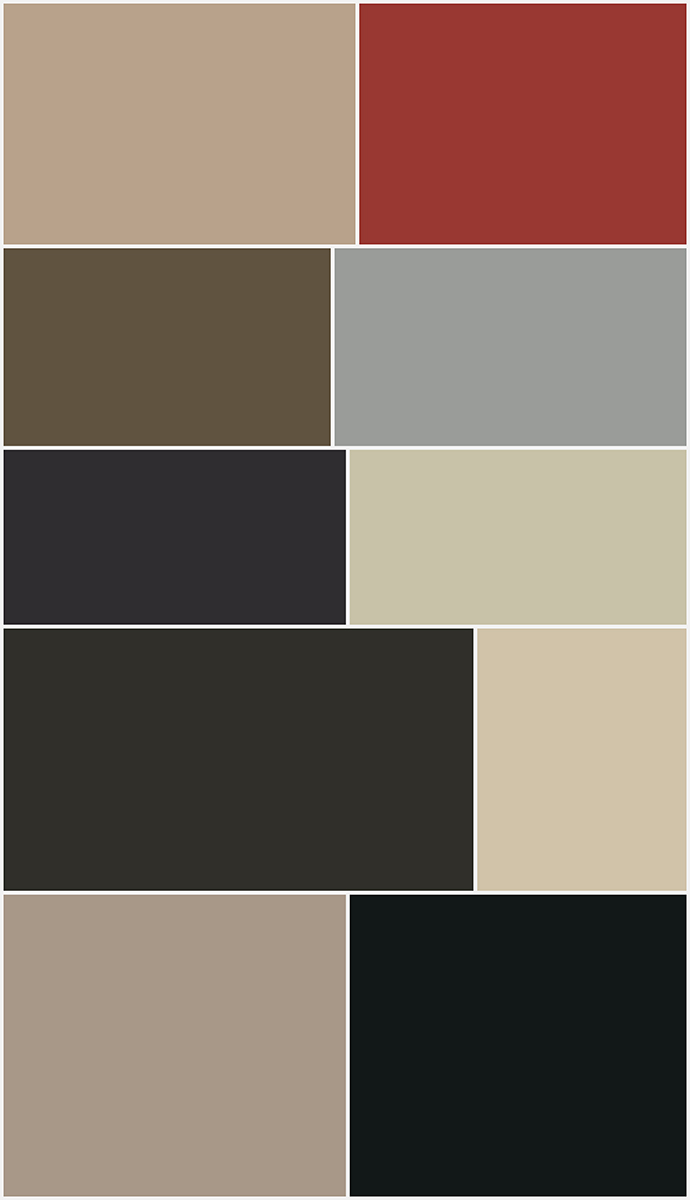

After her initial search for ‘Isis beheadings’ on Google, Šerpytytė looked again. This time, she was confronted only with blocks of colour. A connection error had prevented the images from loading completely. Google’s placeholder displayed whichever pixel was the most numerous: the black of the executioner’s garments, the orange of the victim’s jumpsuit, the blue of the sky, the dull yellow of the sand.

These blocks of colour seemed unsettlingly aesthetic in their graphic arrangements of black, orange, blue, and yellow. Horrifying scenes had been transformed into a composition that recalled minimalist works of art, or the non-representational abstraction of colour field painting, thus raising issues concerning the relationship between aesthetics and violence. This had particular relevance here. As Šerpytytė’s research into Isis had revealed, Isis is aware of the politics of aesthetics. The group is well known for ‘composing’ its violent acts into scenes for media circulation and harnessing specific aesthetic regimes for political purposes. By creating aesthetic objects from these images, Šerpytytė draws attention to Isis’s own politics of aestheticising violence. But in further aestheticising those images, Šerpytytė also asserts how the work is itself, in a way, an act of violence.

This is a deliberate provocation that focuses on the very problematic relationship between the aesthetic, ethical, and political values of art. By making 2 Seconds of Colour avowedly and intentionally aesthetic, Šerpytytė underscores the anxieties surrounding such a relationship. Monumental, unnervingly glossy, colourful, it strikes us primarily as a work of abstraction, complete with all the aesthetic implications that entails. Yet, this is not an autonomous work of art. Speech or writing must accompany it for the work to be fully engaged with – how else can one know what those blocks of colour refer to? Thus, by insisting that the piece requires a verbal supplement, Šerpytytė emphasises how any work of representation is fundamentally an incomplete one: even as a representation attempts to re-present an event, the nature of that presence contains within it an irretrievable absence. Representing the representation of an event, and thus additionally mediating it, Šerpytytė only doubles this inherent loss. As such, she foregrounds the work’s inadequacy in relation to the event it engages with. Moreover, the aesthetic character of 2 Seconds of Colour further complicates such an inadequacy. In its aesthetic dimension, that is, its engagement with the sensate and with affect, 2 Seconds of Colour provokes the question as to how the work could possibly attempt to communicate the affective dimension of a violent event as it was experienced and suffered. And if the event 2 Seconds of Colour deals with concerns unimaginable pain, then how might the pleasure in form that the work elicits be reconciled with this?

These issues are not resolved. Šerpytytė emphasises the sheer awkwardness that arises when a violent and traumatic event is represented aesthetically. 2 Seconds of Colour provokes the viewer to consider the difficulty of confronting and thinking about violence, even as it grants the space to do so. It pointedly resists satisfaction or closure. And if, in its blank, monochrome blocks, 2 Seconds of Colour neither compels the viewer to turn away from images of violence nor consider them voyeuristically, it demands that the viewer actively and critically engage with them.

Aby Warburg once spoke of the importance of denkraum, or ‘thinking space’ that modernity obliterates with its electric speed of communication and encounter. Likewise, with today’s glut of images we cannot think, we cannot act; there is no space to do so. Šerpytytė’s work grants such a space, and seeks to break the closed circuit between violence that is thoughtlessly executed and violence that is thoughtlessly consumed.

Text by Yates Norton

Related exhibitions:

Collecting Hits, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2018Secular Icons in an Age of Moral Uncertainty, Parafin, London, UK, 2017

Focus, Frieze New York, NY, USA, 2017

Absence of Experience, Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017